Politicians in both major parties have expressed concerns that the United States’ national security could be jeopardised should it be unable to manufacture its own clean tech, and that it could fall further behind in an industry that is important for the

renewables-based economy of the future.

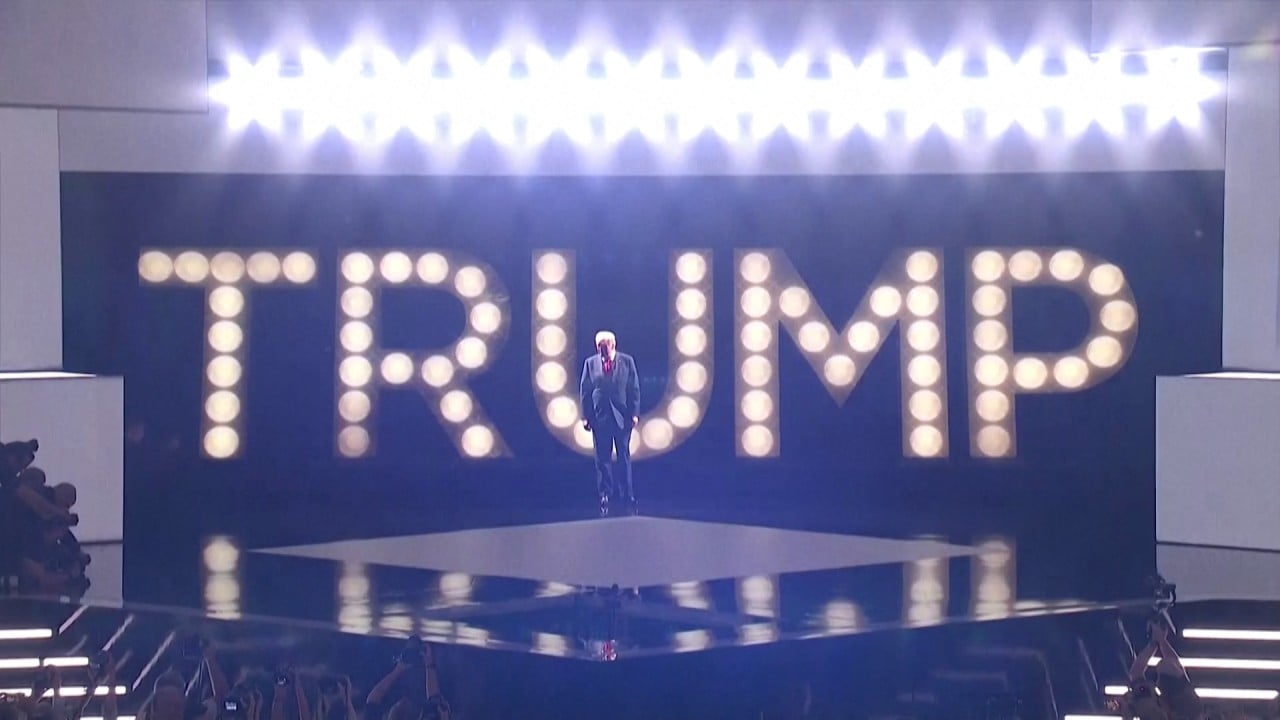

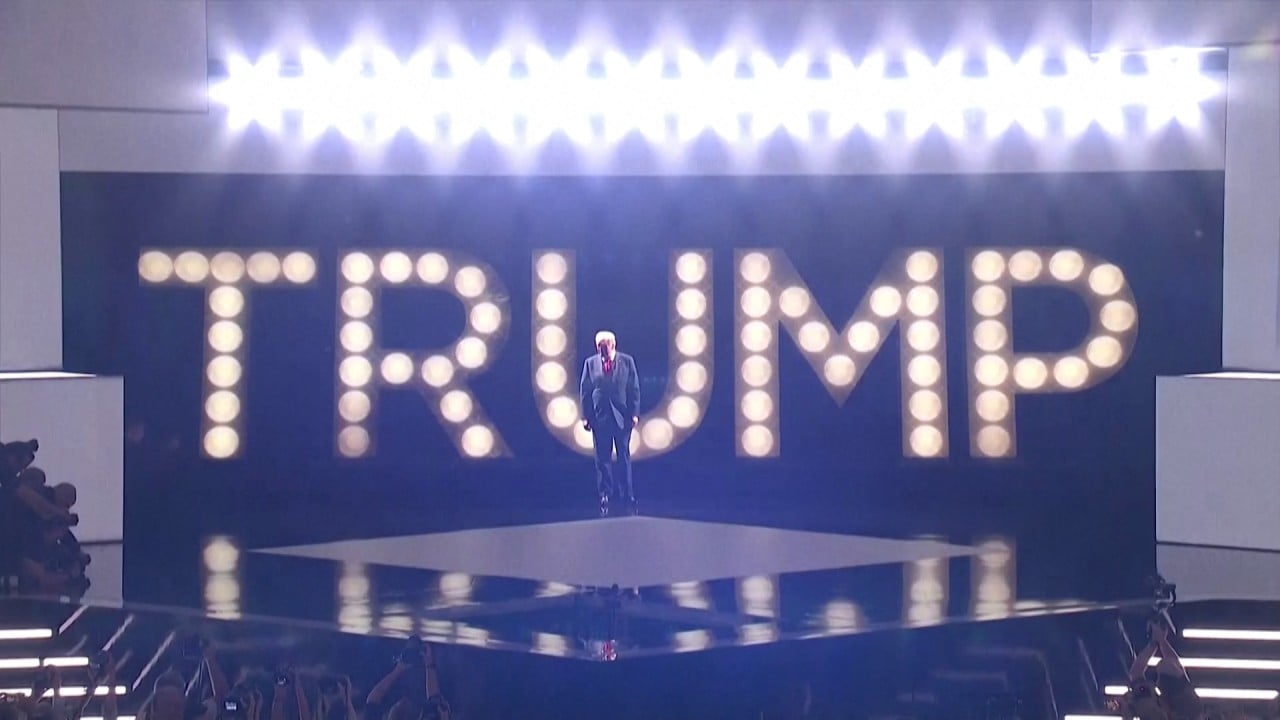

In his second presidential run, Trump has proposed more tariffs: a 10 per cent tariff on every import, a

60 per cent tariff on all Chinese imports and a 100 per cent tariff on all cars made outside the US. This worries many economists because these sweeping tariffs, along with Trump’s other tax proposals, could cost Americans US$500 billion per year, a burden that would be borne disproportionately by lower-income households, which rely more on cheap imports.

Observers may wonder whether the resulting economic headwinds would prevent the US from imposing such high tariffs were Trump to return to the White House. The answer is probably no. History suggests why the government would forge ahead with a policy agenda that would harm average Americans.

02:11

Trump vows high tariffs on China-made cars in his first speech after assassination attempt

Trump vows high tariffs on China-made cars in his first speech after assassination attempt

The US has always valued being on the technological frontier. After World War I and World War II, when other Allied countries sought land and money as war reparations from Germany, the US focused on securing German patents to boost American innovation. And it worked: access to German intellectual property after World War I significantly increased US patents in organic chemistry, a field in which the Germans were world leaders at the time.

A more recent example was the

US-Japan trade war of the 1980s. Back then, many Americans viewed Japan’s rising market share in the semiconductor and automotive sectors as a threat to the US economy. To address concerns, American leaders pursued exceptionally aggressive policies against Japan.

For starters, the Democratic administration of president Jimmy Carter requested that Japanese carmakers build factories in the US. Following that, the Republican administration of president Ronald Reagan imposed 100 per cent tariffs on US$300 million worth of Japanese imports in 1987.

The two trade wars are similar. Back then, like now, the US government sought to secure America’s economic supremacy, an agenda that commanded strong popular support across the political spectrum, despite large net losses to American consumers and firms. The tariffs imposed by the US in both instances violated international rules set by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and its successor, the

World Trade Organization.

Even the recent political rhetoric against China, which warns of future

military conflict in the Taiwan Strait, echoes the Japan-bashing of the 1980s, which often hearkened back to World War II.

But there are important differences between the two cases. Japan depended entirely on the US for its military defence in the 1980s. American political leaders were therefore confident that any pressure campaign – whether reasonable or not – would ultimately be successful. There is no such assurance with China.

13:04

What does it mean for the world when Chinese consumers tighten their belts?

What does it mean for the world when Chinese consumers tighten their belts?

China’s ability to respond to US demands is also limited by its domestic concerns. In 1990, per capita income in Japan and the US was at a similar level, whereas Chinese per capita income is much less, currently around 17 per cent of the US level. The Chinese government has invested heavily in

lifting its population into the middle class and establishing itself as a global leader in hi-tech sectors, which will limit its room for manoeuvre.

At a time of huge political uncertainty, one thing is clear: the US government will maintain its aggressive stance towards China, a policy that, as with Japan in the 1980s, has bipartisan support. But while Japan conceded to most of America’s demands, China may not be willing or able to be so obliging. Chinese and US leaders will need to recognise each other’s aims and limitations if they want to avoid tremendous economic losses for their people.

Nancy Qian, professor of economics at Northwestern University, is co-director of Northwestern University’s Global Poverty Research Lab and founding director of China Econ Lab. Copyright: Project Syndicate