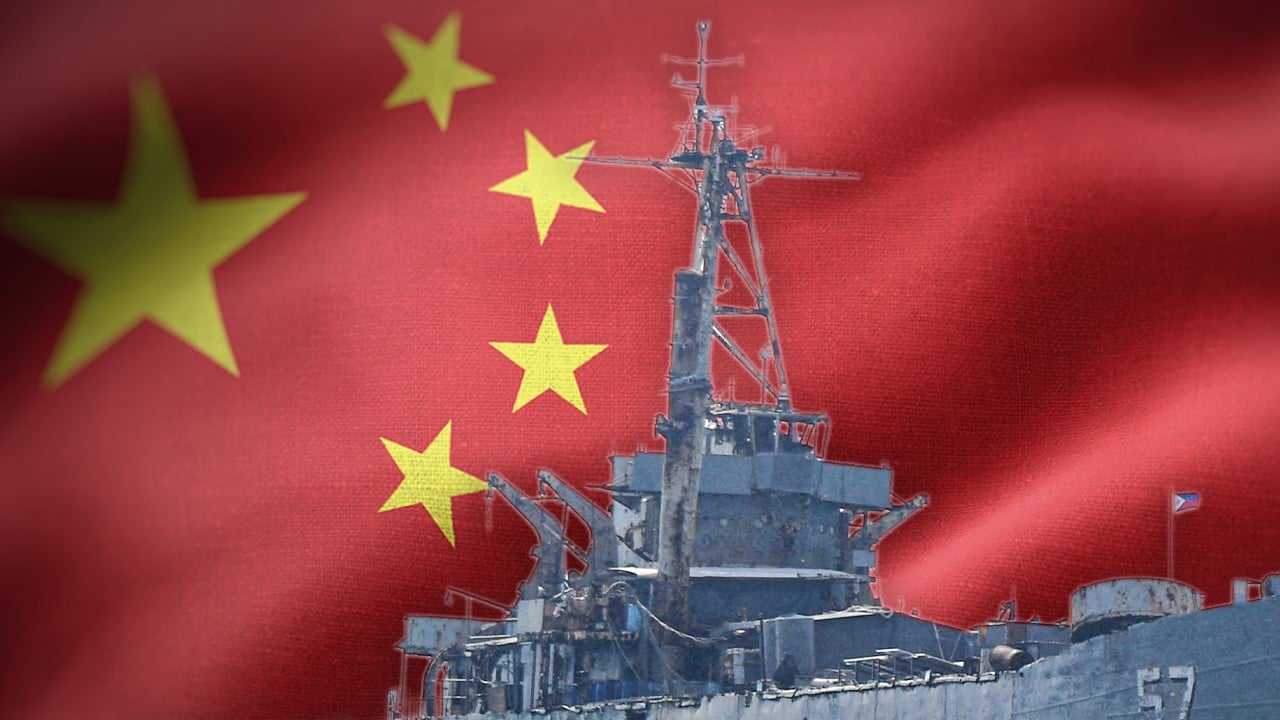

South China Sea: Beijing ‘wary’ as Japan deepens defence ties with Vietnam, Philippines

Vietnam defence chief General Phan Van Giang called for the two countries to push ahead towards a “new, effective phase … for peace and prosperity in Asia and the world”, Vietnamese media reported.

Manila called the drills “part of the ongoing efforts to strengthen regional and international cooperation towards realising a free and open Indo-Pacific”, according to a statement from the Philippine armed forces.

Collin Koh, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, said Japan’s move to provide security-related material to Vietnam was not surprising, given that it has previously offered coastguard aid.

But it was a “notable step”, he said, as the recent arrangement was directed by Japan’s defence ministry compared to past instances which were led by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

JICA is a government body which traditionally focuses on economic and social assistance to developing countries, but in recent years it has been involved in programmes related to maritime security.

The move, Koh suggested, was an example of Japan tailoring its Vientiane Vision – a defence initiative that guides Tokyo’s cooperation with members of Asean (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) – to Vietnam’s needs.

“Hence, it starts with non-lethal and relatively low-tech or unsophisticated material in the form of logistics vehicles,” he said, referring to the supply transport vehicles.

“I believe this is a test balloon. This latest transfer may potentially elevate to the transfer or sale of more sophisticated equipment in the future, such as radars.”

China would be “wary” of this development, Koh said, noting that Japan has close economic ties and growing security links with Vietnam.

“I think Beijing will have come to the long-term assumption that Tokyo would some day in the future transfer or sell lethal arms to Vietnam,” he said.

Greg Poling, director of the Southeast Asia programme at the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said the recent agreement between Japan and Vietnam may be a sign of a deepening security relationship.

As for Japan’s recent maritime exercise with the Philippines, Poling said it was “just the latest in a string of security developments in [their] security relationship”.

Tokyo and Manila believe they face a shared threat in China and are responding accordingly

“Tokyo and Manila believe they face a shared threat in China and are responding accordingly,” Poling said. Japan has competing claims with China in the East China Sea.

“The only thing Beijing could do now to halt that deepening partnership would be to stop using force and the threat of force in its maritime disputes, which is unlikely under Xi’s leadership,” he said.

Prashanth Parameswaran, a fellow with the Washington-based Wilson Centre’s Asia programme, said the recent defence interactions between Japan and Southeast Asian states pointed to Tokyo’s growing security role in the region, which “complicated China’s quest for greater regional dominance”.

“China may prefer the status of regional hegemon in Southeast Asia, but its own actions are leading countries to seek options elsewhere, including Japan, to balance its growing influence,” said Parameswaran, who is also founder of a newsletter on regional developments called Asean Wonk.

“Japan’s greater security role in Southeast Asia is slowly but surely becoming clearer.”

Lyle Morris, a senior fellow at Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis, called the Japan-Vietnam agreement “significant”, saying it is an illustration of Japan’s increasing role in supporting military technology transfers to South China Sea claimants.

Morris suggested the recent developments would be seen as a “concerning trend” for China, which he said “did not like ‘external powers’ to intervene” in the territorial disputes.

“It suggests that claimants are eager and willing to engage other powers in the region to bolster their own defence capabilities. I would imagine China will lodge a diplomatic protest with Japan and urge Japan to stay out of the dispute and not complicate the situation,” he said.

Koh said China might seek to counter such regional security arrangements with its own outreach – but so far that has brought limited success.

“This is also a strategic reality that perhaps Beijing has come to terms with … that there will be limitations to these outreaches for defence and security engagements with its Southeast Asian South China Sea rivals who appear more at ease having such engagements with extra-regional powers that clearly are designed to balance against China’s moves,” he said.

But, Koh noted, while Beijing would be wary of the recent developments, it “may not be overly worried” as it appeared to consolidate its “physical position” in the South China Sea with its rapid military and coastguard build-up.

“Beijing appears to exude a certain flair of confidence of its ability to handle extra-regional presence,” he said.

Zhou Bo, a senior fellow at Tsinghua University’s Centre for International Security and Strategy, said the deepening ties between Japan and Southeast Asian countries reflect a shift in Tokyo’s diplomatic strategy.

He said this stems from Japan’s concern over a possible use of force by China in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait, which he called “unreasonable”.

“[Japan’s] judgment of the regional situation has led to its desire to interact with those countries that have conflicts with China,” said Zhou, who is a retired PLA senior colonel.

However, he added that Japan’s recent agreement with Vietnam was “not a big deal”.

“I don’t think these [military] aids will play any role in changing the situation in the South China Sea,” he said. “It’s just a drop in the bucket. [China] does not need to respond to it.”

Zhou stressed that China has always faced interference by “foreign forces” in the South China Sea.

“This sort of opposition [towards China] is inevitable in that they believe they have a stake in the security of the South China Sea. But since no one is impeding freedom of navigation, it won’t necessarily have a big impact,” he said.