Children and elderly people tortured at Syria military prison, Paris court told

Witnesses have told a Paris court how children and elderly people considered enemies of the ruling Syrian regime were tortured in a notorious military prison, at the trial of three high-ranking officers close to the country’s president, Bashar al-Assad.

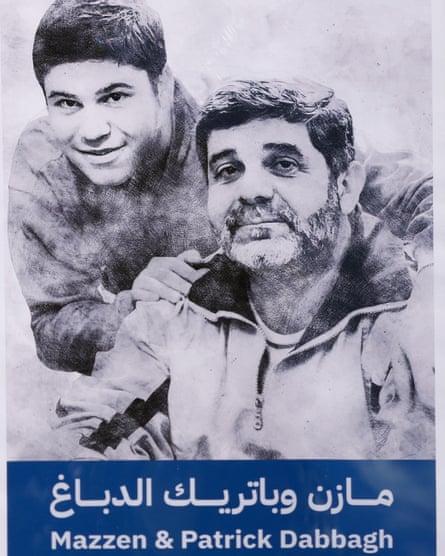

The three are being tried in absentia for crimes against humanity and war crimes in connection with the deaths of two French-Syrian dual nationals, Patrick Dabbagh, a 20-year-old student, and his father, 48.

Ali Mamlouk, 78, the head of the Syrian secret services and security adviser to Assad; Jamil Hassan, 72, who was head of the Syrian air force intelligence unit until 2019 and a member of Assad’s entourage; and Abdel Salam Mahmoud, who is in his early 60s and is intelligence director at the notorious Mezzeh detention centre where the father and son are believed to have been held, are accused of complicity in their arrest, torture and deaths.

The trial at the Palais de Justice, a first in France, highlights the determination of European states to prosecute crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows countries to try perpetrators regardless of their nationality or where the crimes were committed.

The accused will not be in court but campaigners say the case bolsters calls for universal justice for the families of more than 111,000 people who have disappeared in Syria since 2011.

The case was brought to France’s special war crimes tribunal by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), the Human Rights League of France and the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression.

Patrick was arrested by members of the Syrian air force intelligence unit on 3 November 2019. Mazzen Dabbagh was taken the following day. Both are believed to have been held at Mezzeh prison. In 2019, the Syrian authorities issued certificates stating Patrick had died in January 2014 and Mazzen in November 2017. No causes of death were given and the bodies were not returned to their family.

Obeida Dabbagh, 72, told the court his brother Mazzen, who worked as an education counsellor at the French lycée in Damascus, was the youngest of five sons and had “never had any problems with the Syrian intelligence services”.

“Mazzen was the only [brother] who wanted to stay in Syria. He was close to our mother … he was very much a family man.”

Mazzen studied literature at the University of Damascus, married a neighbour’s daughter and had two children.

Obeida said he was living in France at the time of his brother’s and nephew’s arrest and did not hear the news until several days later.

“The Syrian officials who came to the house said they wanted to interrogate Patrick … they took his phone and computer but they said, ‘Don’t worry … it’s a matter of a few days’. The following day the same men came again but with more people and told Mazzen ‘you have badly educated your son and we must interrogate you’.”

Mazzen’s brother-in-law who lived next door questioned why they were taking him away and he was also arrested.

“At the prison, they were taken this way and that and the last he heard was Mazzen shouting, ‘I’m suffocating, I’m suffocating get me out of here’. These were the last words any of us heard from him. There were no words, no information since.”

Obeida said he had no idea why the pair were arrested and could not rest until he found out “the truth of what happened”.

Earlier in the four-day hearing the court was shown photographs in the Caesar files created by a Syrian police official who fled the country in 2013, showing the bodies of prisoners who had been beaten and died.

The files contain about 54,000 such photos of an estimated 11,000 victims of all ages and origins held at different regime detention centres, and have been recognised by European courts and used by experts in cases.

In the Paris trial witnesses have described the violence inflicted on prisoners at the Mezzeh military prison. One former prisoner, who did not wish to be named, said he spent three months in Mezzeh and told how prisoners in their 70s and young children were tortured there. He described having electric shocks administered to the genitals, his body burned with cigarettes, and prisoners hung by their hands or feet for days.

“I have lost 20 members of my close family including two brothers. I don’t know the exact number, probably more, because I still have relatives in jail,” he said.

Clémence Bectarte, a French lawyer representing the Dabbagh family and the FIDH, said witnesses had spoken of children as young as 10 years old being tortured at Mezzeh.

The Syrian conflict began with pro-democracy protests in 2011 and escalated into civil war, with a mass uprising against Assad the following year.

More than 15,000 Syrians are believed to have been tortured to death by intelligence officials. More than 230,000 civilians, including 30,000 children, are reported to have been killed in the conflict, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

Assad has been rehabilitated in the Arab world over the past 12 months, invited to Arab League summits and meetings with other regional leaders.

In November last year France issued an international arrest warrant for Assad for the use of chemical weapons against civilians.

Three others, including Assad’s brother, Maher, were also indicted over the use of sarin gas in two 2013 attacks that killed more than 1,000 people, including hundreds of children.

Trials of Syrians have taken place in the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden, but it is the first time such high-ranking figures close to Assad will be held to account.

France set up a specific war crimes unit in 2012, but until now the principle of universal justice has been constrained by the requirement for either the accused or the victim to have a tangible connection to France, through nationality or residence.

Obeida added: “I have never given up fighting for them to know what happened to them … they are symbols of the repression in a country they loved, they never wanted to leave. They could have come to France but they did not want to. They wanted to live in Syria. Destiny decided otherwise. I hope the international community can one day bring to justice the head of that country.”