Don’t expect big changes in France’s China policy, at least not yet

There is a high level of collaboration in the aeronautics sector, in particular with Airbus having a major foothold in the Chinese market. The same can be said of the nuclear energy sector, in which France has long played a role in furnishing China with technical know-how.

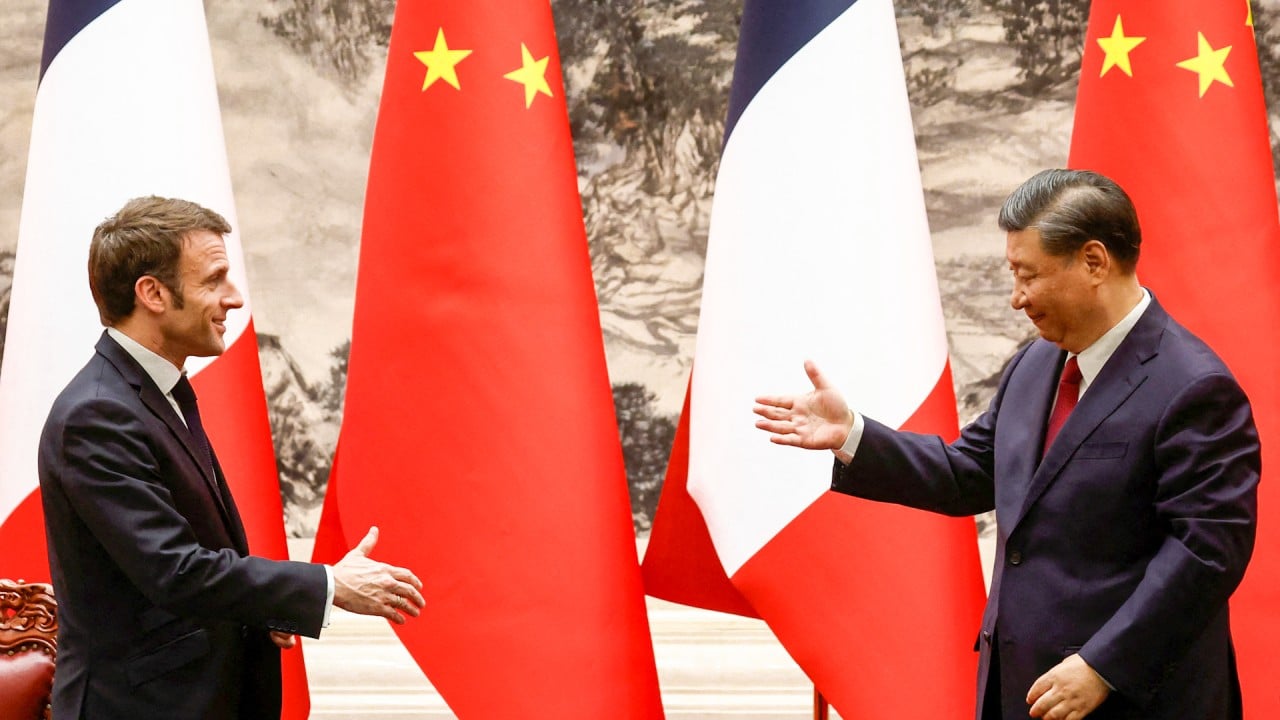

No matter who controls the French legislature, these interests will not go away overnight. Nor, for that matter, will Macron, who’s poised to remain president until 2027. As the pre-eminent authority in deciding the nation’s foreign policy, he can be expected to stay the course when it comes to cooperating with China.

The legislature can exert some influence over foreign affairs. But even here, there’s a couple of reasons to think this won’t have much of an effect. First, the French legislature is thoroughly divided. While the left-wing coalition, the New Popular Front, has the largest plurality of seats, its 188 legislators still puts it far from the 289 needed for a majority, and not far ahead of the centrist Ensemble’s 161 seats and third-place National Rally’s 142.

So unprecedented is this situation – France has never had a hung parliament in its modern history – that no one is fully sure who Macron will appoint as prime minister. He has called upon “republican forces” – code for centrist parties – to build a broad majority that he can select one from. Forging a coalition with just enough representatives to pass legislation just might work.

It also might not, since it will be very difficult to cobble together a bloc capable of functioning without the support of either National Rally or the leftist coalition who Macron has signalled he does not want in government. Either way, a legislature this at odds with itself will find it difficult to sway the president’s position on China.

Melenchon’s position is in sharp contrast to the centre-left Socialist Party, the second-largest party in the leftist coalition. Over the past few years, it has arguably been the most anti-Beijing party in France, having put forth the motion on Xinjiang in 2022. But the strategy it used to get that vote passed – teaming up with the centrist parties, including the president’s – would be less likely to succeed today, in a parliament more dominated than ever by National Rally and France Unbowed legislators.

National Rally is equally difficult to pin down. Members of the party have abstained on or opposed votes condemning China in the European Parliament, but also claim they will take a tougher stance on the trade imbalance and Chinese expansionism.

The party, so it seems, wants it both ways: to style itself as a defender of European values against China, as well as to keep open the door for collaboration should it end up seeking greater independence from the European Union and the US.

A subtle albeit important factor here is whether they end up working with the centre-right Republicans, who have been debating if they should cooperate with National Rally. The Republicans have recently sought to amplify public concern about suspected Chinese hackers, undermining Macron’s more diplomatic position. If National Rally ends up relying on their votes, it may have the effect of pushing that party in a more unambiguously anti-China direction.

However, one might suspect that, given the power Macron wields over foreign policy and how unwavering he’s been, such a shift would need to wait until after 2027, when a new president is elected. Until then, it seems likely that France will continue to heed de Gaulle’s supposed view of China as a “gigantic thing” that we cannot afford to ignore, “since it exists more and more”.

Conrad Bongard Hamilton is a postdoctoral research fellow with the School of Politics and International Relations at East China Normal University in Shanghai