What can Hong Kong learn from Silicon Valley in push to create I&T start-up hub?

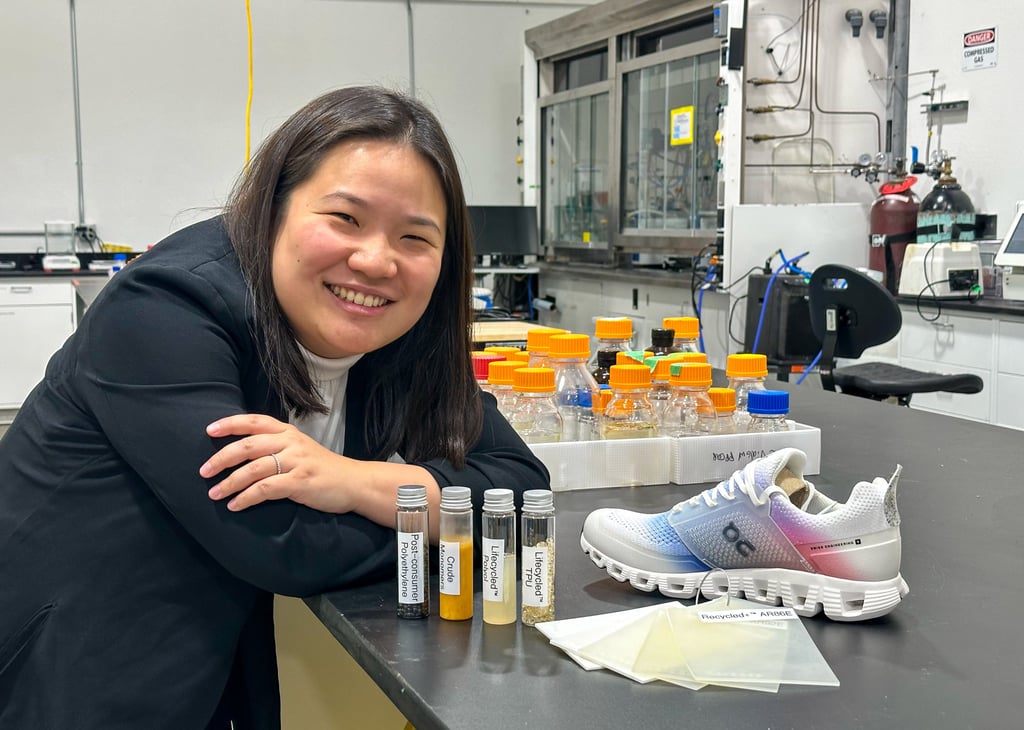

Wang, 30, told her Hong Kong visitors – a group of officials led by finance chief Paul Chan Mo-po – how the company had expanded, opening a pilot chemical recycling plant in India.

Chan, who visited California in May, was quick to suggest that Hong Kong would be a good location for the growing start-up, as the city offered access to mainland China and other parts of Asia.

Wang told the Post afterwards the city was worth considering as a research lab base in Asia, for its proximity to the mainland’s thriving tech scene.

Neighbouring Shenzhen, sometimes called the “Silicon Valley of China”, is home to tech giants Tencent and BYD and drone company DJI, and the mainland’s leader in patent production.

“Silicon Valley is not a place where it’s easy to keep a company alive,” Wang said. “What keeps everybody going is having like-minded people who also have the internal resources to share among each other, and the social support to keep going.”

The southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area is renowned for an ecosystem that motivates entrepreneurs with fresh ideas to dream big. Intel, Apple and Google are just three among many that went from humble beginnings in Silicon Valley to phenomenal global success.

A beacon of hi-tech innovation after decades of crises and triumphs, it holds valuable lessons for Hong Kong in the city’s quest to become an international innovation hub.

The Post asked Wang and two Silicon Valley tech veterans with Hong Kong ties what the city needed to do to achieve that goal.

Top of their list: change the mindsets of investors and tech geeks and strengthen university-industry ties to boost the start-up ecosystem, and leverage the city’s strength in the Greater Bay Area which includes Macau and nine cities in Guangdong province.

Big dreams and persistence

Born in Qingdao, Shandong province on the mainland, Wang moved to Canada with her family and grew up in Vancouver.

She was in high school when she paired up with her best friend, Jeanny Yao, for a science fair project that sparked their interest in plastic upcycling, finding new ways to reuse a stubborn item of rubbish.

Novoloop was born from their teenage dreams. Wang went on to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania’s molecular biology programme, while Yao studied biochemistry and environmental sciences at the University of Toronto.

In 2015, a year before graduating, they co-founded BioCellection in Silicon Valley with the backing of an American venture capital firm and university funding programmes.

That start-up became Novoloop where Wang is CEO and Yao, the chief operating officer.

“We don’t have PhDs. We don’t have a lot of resources. We’ve been very bootstrapped for a long time,” said Wang.

At Menlo Park, they discovered the “magic” of its robust venture funding landscape.

Describing how the start-up scored critical breaks along the way, Wang recalled: “The local newspaper came and wrote a story about us, it got distributed to a bunch of people or tech billionaires, right to their doorstep.

“You don’t need everyone to say yes. You just need that one person to say, ‘I will bet on you and help you’. That’s what it takes, you just keep going.”

Novoloop has raised US$27 million so far, but Wang described Silicon Valley as a “pressure cooker” where entrepreneurs faced stiff competition, high rents and hefty labour costs.

If there is a lesson for Hong Kong from Wang’s experience, it is that young tech entrepreneurs need plenty of support through a journey that can take years.

The shrinking US funding market in the economic downturn prompted Novoloop to look for cheaper supply chain components. With the pilot plant in India to scale up manufacturing capacity, the firm has ambitious plans to expand across China and Asia.

Hong Kong, now on Wang’s list of places to consider, is home to 4,257 start-ups, many of which have founders from the mainland, the United Kingdom and the United States, according to InvestHK’s 2023 Startup Survey.

The sector employs 16,453 people, primarily in fintech or e-commerce.

Investors willing to ‘try the unknown’

David Liu, 42, founder and CEO of Deltapath, a unified communications company offering solutions to a wide range of industries including healthcare, retail, energy and contact centres, knows Hong Kong.

Born in San Jose, California, he lived in Hong Kong for some years before going to study at Santa Clara University in the early 2000s.

In that era before smartphones, he developed a way to call his parents in Hong Kong free of charge. It was the first-generation internet-based phone system, known as Session Initiation Protocol.

That personal project inspired him to start a tech company in Santa Clara in 2001, three years before he graduated from college. His first customers were businesses eager to save on costly international calling bills.

Since then, the company has grown to about 50 employees globally, with offices in Auckland, Tokyo, Singapore, Taipei and Hong Kong.

One recent project was upgrading the Hong Kong government’s 1868 hotline, which residents can call from anywhere outside the city for help in emergencies without incurring roaming charges.

Liu said there was a significant difference in mindset between Hong Kong and Silicon Valley, particularly among potential customers and investors.

He recalled that some years ago, the Office of the Government Chief Information Officer invited Deltapath to pitch its communication solutions to various departments in the city and the session was held at Cyberport.

Liu said that after his demonstration, the government officials kept asking him: “Who else is using it?”

Hesitant to be early adopters, they wanted a proven product. This, he said, underscored a conservative mindset that permeated in the city’s private sector as well.

In contrast, he said, Silicon Valley investors were prepared to take a risk and “try the unknown”.

“They have the culture of investing in the future,” he said. “When they play it very safe, new start-ups don’t get a chance.”

Liu said that in 2004, three years after founding his company, Juniper Networks, regarded as a major competitor of Cisco, became one of Deltapath’s first customers and adopted its solutions.

He said some Silicon Valley investors were high-net-worth individuals who had exited tech giants such as Yahoo and Microsoft and did not include a proven track record as a key criterion for putting their money into a start-up.

“If they like the idea, the management and the founders, they give them a chance and then see what happens,” he said. “That is one of the key drivers in Silicon Valley.”

Liu had one more observation about Hong Kong’s tech hub ambitions: the city had to enlarge its talent pool.

He said it had been hard to hire local graduates for his Hong Kong office located in Central. His employees hail from diverse backgrounds, including those from India and the Philippines.

He felt the problem began in the city’s universities, which did not have enough of the best local students doing the right courses in computer science.

“The culture in Hong Kong is to go into finance and banking, or become a lawyer or a doctor,” he said. “The top students don’t really think about computer science. So in the end, you don’t have a good supply of tech people.”

Universities rely less on government

Hong Kong entrepreneur Alfred Chuang, who founded Silicon Valley venture capital firm Race Capital in Palo Alto, said the issue was not only the number of students doing the right subjects, but also the strength of ties between universities and industry.

In Silicon Valley, tech firms recruit actively from a diverse pool of talented students, not limited to those studying technology.

“Hong Kong also has many bright students. But it’s different from the US in that it doesn’t have the culture of endowments which drives entrepreneurship” Chuang said.

Stanford University, one of the key brains trusts for Silicon Valley’s tech firms, had a US$36.5 billion endowment as of last August. In 2022-23, it drew US$1.9 billion from that to support operations, accounting for nearly a quarter of its annual operating budget.

The endowment also enabled Stanford to invest heavily in encouraging entrepreneurship through dedicated programmes which provide capital and mentorship to student-led firms. Alumni and faculty have created more than 39,900 companies, according to the university, including Google, Cisco, LinkedIn and Netflix.

Stanford relies much less on the government. Federal research funding of US$1.3 billion accounted for about 16 per cent of total operating revenue.

In contrast, Hong Kong’s public-funded universities have significantly smaller endowments, and rely heavily on government support.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), for example, has donations of HK$126 million (US$16 million) – less than 2 per cent of its annual operating revenue for the year ended in June last year.

Government subventions of HK$3.3 billion made up almost half its annual income.

Chuang, who advises City University’s school of business dean’s committee and HKUST’s school of engineering industrial advisory committee, was optimistic that Hong Kong could close the gap.

“Hong Kong started much later than the US elite universities. But catch-ups can be quick,” he said. “We should educate locals how their donations can encourage bright students in grad schools to commercialise their innovations.”

‘What a waste to disregard mainland’

His venture capital firm invests in early-stage start-ups, focusing on data, artificial intelligence and machine learning. He also runs a US-based non-profit, FoundersHK, to connect tech leaders in California and Hong Kong.

A recent survey by his group showed that nearly half of Hong Kong start-ups targeted the US or Europe as their go-to-market, and some chose emerging markets such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

“Very few considered mainland China, which I think is quite worrying” he said. “When you ask them where they trial-run their products, they tell you Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud and Oracle. No one thinks of using tech stacks on the mainland.”

He pointed out that the hardware and software markets in the US were able to grow fast because of the country’s large, self-sustaining domestic market.

“Outside the US, only China’s consumption market is comparable. What a waste if Hong Kong tech firms don’t consider this market,” he said.

He felt the Greater Bay Area could become a “desirable go-to market” for Hong Kong-born innovation.

In 2022, the Hong Kong government outlined a policy blueprint to develop the city into a global innovation and technology centre. Major directions included consolidating its role as a bridge between the mainland and the world.

Asked what else the Hong Kong government could do, Chuang said: “My answer is that in the US, no one relies on the government in terms of policy and resources.

“Hongkongers have become used to playing up the insufficiencies of the government. That has resulted in the creation of government-led task forces, which I don’t see as a way out.”

A frequent traveller between Hong Kong and San Francisco, he was thrilled to see “a very vibrant tech scene” in the US due to the artificial intelligence boom.

Looking ahead, he said Hong Kong had the potential to leverage its unique position to create innovative solutions applications for American and mainland platforms, while the San Francisco Bay Area would remain the undisputed epicentre of AI in the near future.

Despite the Joe Biden administration’s earlier ban on certain US tech investments in mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau, he said he believed there was still leeway for the city.

“The strengths of Hong Kong start-ups have been their flexibility to shift between the two markets, for instance, achieving something seemingly impossible on the mainland due to the geopolitical tensions,” he said.

“If they can manoeuvre well, it will prove Hong Kong’s magical uniqueness.”