China to host new round of Hamas-Fatah talks but its influence ‘may be limited’

The Washington Post noted that the meeting follows an agreement between Israel and Hamas – after sporadic talks – that control of Gaza would be handed over to a new Palestinian force in the event of a ceasefire.

Despite Beijing’s statement that the factions had an “in-depth and candid dialogue”, neither Hamas nor Fatah announced any breakthroughs after the April meeting.

On Tuesday, Lin said China had “consistently supported reconciliation and unity among Palestinian factions through dialogue and consultation” and was willing to “provide a platform and create opportunities” for their engagement.

“China is ready to strengthen communication and coordination with them … to work together towards the goal of intra-Palestinian reconciliation,” he said.

Like most countries that recognise Palestine, China regards the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority led by Fatah as the legitimate government.

But Beijing has also maintained close communication with Hamas, which controls the Gaza Strip and has had strained relations with Fatah for years. China’s stance has hampered its mediation role in the Gazan conflict.

China has also been strongly critical of Israel during the war in Gaza, which was sparked by the October 7 Hamas attack in which some 1,200 people were killed and 251 taken hostage.

Since then, nearly 39,000 Palestinians had died as of Monday, according to the Hamas-run health authority in Gaza, which added that at least 80 people were killed on that day alone.

Liu Xinlu, director of the school of Arabic studies at Beijing Foreign Studies University, said the talks may yield “some degree of reconciliation”, as both sides sought to extract political capital ahead of a ceasefire.

A poll conducted in May by the Palestinian Centre for Policy and Survey Research found Hamas twice as popular as Fatah in the West Bank, while support for Hamas in the Gaza Strip was at 38 per cent, compared with Fatah’s 24 per cent.

“The will for internal reconciliation is strong on both sides, with Hamas needing more support and political resources and Fatah wanting to seize the political and moral high ground,” Liu said.

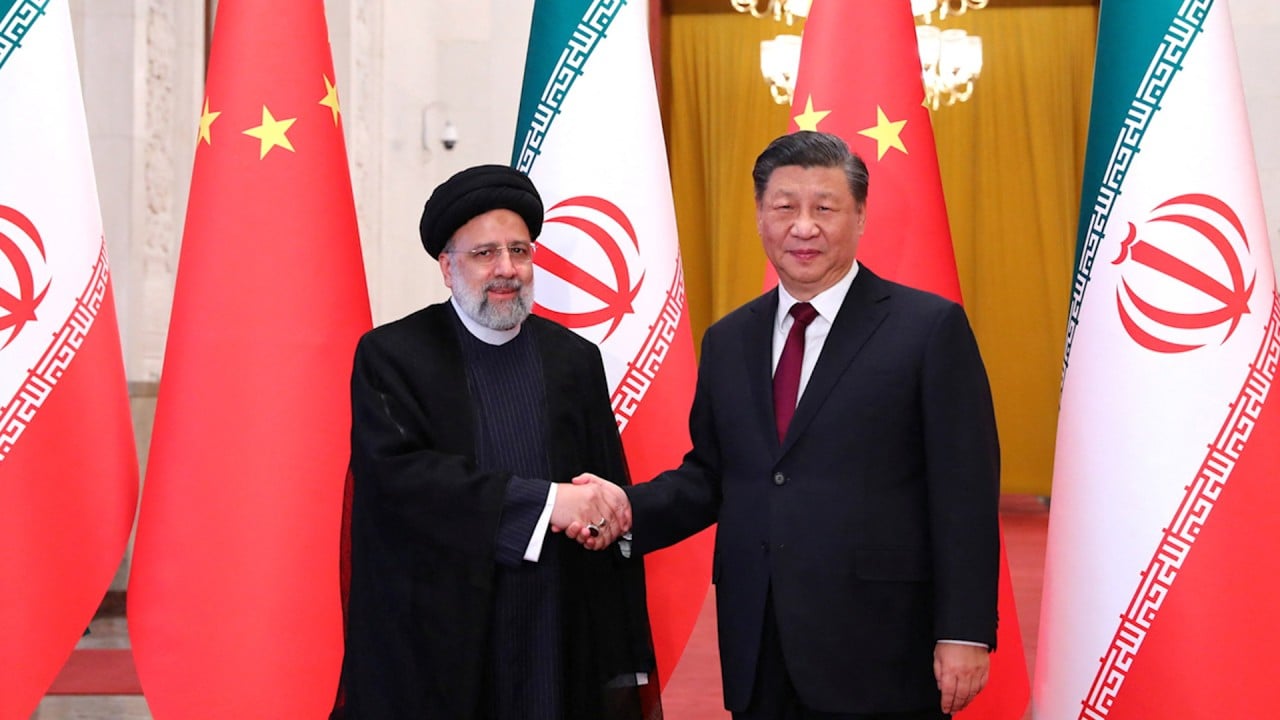

“So I think there is a high possibility that the two factions can reach a so-called reconciliation, or at least expressing an attitude, like the [Beijing-brokered] Saudi-Iranian normalisation [in March 2023].

“China is neither a creator nor a party to the problem. It has always advocated Arab, intra-Arab and intra-Palestinian solidarity and cooperation, so it is well suited to serve as a platform for [the talks].”

James Dorsey, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, was less optimistic. He noted Beijing’s limited leverage over Israel, which ultimately would decide the Gaza governing body’s future.

“A permanent ceasefire and [establishing] a Palestinian administration [in Gaza] are two different things. Because the key issue is going to be whether [the new Gazan administration] is under Israeli tutorage,” he said.

“The Israelis demand the rubric of security [in Gaza]. But China has no clout in that and it has no leverage [on Israel].”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has so far rejected calls to include the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority in a post-war Gazan government.

Netanyahu’s comments that he would not “replace Hamastan with Fatahstan” have cast a shadow over hopes for a viable future of the Gazan authority.

According to Dorsey, Israel has “thrown out some ideas” on governance in Gaza, “but they refuse to issue a real plan for the day when the fighting stops”. They have “made it very clear that they don’t want to see the Palestinian Authority take over Gaza”.

“China has been very critical of Israel’s conduct in the Gaza war, and in Israel’s perception China has allowed a lot of antisemitism expression on social media. So, China is not the party that can swing Tel Aviv, certainly not like Washington,” he said.