Standing on a truck after a helicopter dash to the tiny airport of Barbuda after Hurricane Irma, prime minister Gaston Browne addressed the people. He declared all must leave the Caribbean island for their own safety as Hurricanes Jose and Maria were predicted to soon hit. They would be allowed to return “when it was safe”.

It was 2017, and the destruction of Barbuda was reported worldwide to be “catastrophic”, with homes, infrastructure and livelihoods decimated and the island’s inhabitants left in despair.

A state of emergency was declared and the evacuees restricted to the more populous sister island of Antigua for 30 days. Browne said Barbuda was 95% destroyed and estimated it would take up to $300m (£245m) to rebuild.

Within a week, heavy machinery and workers were clearing land for construction. However, they weren’t building homes but a private airport for billionaire US investors who had luxury mansions and exclusive hotels planned. Their plans appeared to have been fast-tracked by the government, sidestepping conventional approval processes, and ignoring the need for environmental impact assessments.

Hurricane Irma’s destruction opened an opportunity for advancing what have been called the most egregious land grabs in the Caribbean, as developers – enabled by politicians’ thirst for foreign direct investment – have sought to turn Barbuda into what Gaston Browne called an exclusive club “only for billionaires”.

The population of about 1,700 has been fighting back against what they claim is an erosion of their unique communal land rights, which has exacerbated social and economic disparities, as well as corruption, human rights violations and environmental crimes.

The UN body on human rights has expressed “deep concerns” over the sprawling resort being built for the uber-rich, and islanders are now awaiting a case which will go before the privy council in November, a challenge brought by two Barbudans over the legality of the airport’s construction, which has already cut into acres of virgin forest.

This month, Browne spoke at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in Germany, saying it was time for “legally binding obligations” on the environment rather than “abandoning peoples to suffering and destruction”.

In New York on 23 September, he gave a speech calling for a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty to be negotiated at the UN. Yet in Barbuda, governmental decisions have been steamrollering over objections from local people who believe their island is at risk of irretrievable ecological damage.

The Caribbean islands of Antigua and Barbuda achieved independence from the UK in 1981, but remain in the Commonwealth with a constitutional monarchy under Charles III, so the privy council is the final court of appeal. It will decide whether Barbudans affected by projects such as the airport have the legal right to challenge the government in court.

Marine biologist John Mussington is chair of the Barbuda Council’s agriculture and fisheries division. “Barbuda was not uninhabitable after the hurricane. This was furthest from the truth,” he says. “Neither was it 95% ‘destroyed’. The UN development project damage assessment said that it was 95% ‘damaged’. There is a difference between destroyed and damaged.

“The intention was to remove all of us and not allow us to come back to Barbuda. Without a population, redevelopment could happen on a clean slate – terra nullius (territory without a master).”

Historically, land in Barbuda is owned by the population – a people who have worked the land for generations. Evidenced by centuries of occupation and tenure, each Barbudan had been considered a stakeholder with a say in how land was developed and the right to use it.

Communal ownership dates from when the Codrington family, leaseholders of Barbuda since 1685, left compensated with a payment of £8,823 8s 9d under the Slave Compensation Act 1837 for the loss of 411 enslaved people. Those who had been chattels of the Codrington plantation were left to survive however they could. Over the years, anthropologists have documented how communal land has played a vital role in the way of life of Barbudans since.

The island’s pristine landscapes have long drawn visitors, including Diana, Princess of Wales, after whom an 11-mile pink sand beach is named. The beach, along the western boundary of the Barbuda Lagoon, is just one area under threat, as rising seas and poor land management contribute to the relentless erosion of the sandbar protecting the beach.

The 16-mile (26km) Codrington Lagoon national park (CLNP) is another treasure. It encompasses rare mangrove thickets and expansive seagrass beds, inter-tidal expanses and coral reefs. Marine life thrives, with the hawksbill and leatherback turtles among the endangered species claiming sanctuary. Above the azure waters, the largest gathering of frigate birds in the western hemisphere appears daily.

CLNP is a formidable bulwark, exemplified during Hurricane Irma, when the lagoon acted as a shield against coastal erosion.

The park is protected under the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, a conservation treaty signed by nearly 90% of UN member states, including, since 2005, Antigua and Barbuda. But critics claim the agreement is not being upheld.

“Evidence of poor land and marine management can be seen in the many ill-conceived developmental projects in progress across the island,” says Mussington.

“Mangroves in construction zones are being transplanted in the mistaken belief that removal will have no ecological impact. Sand dune vegetation, nature’s hurricane soil defence, is being removed to facilitate hotels, golf courses and mansions. Approved by the government, these projects have altered the coastal dynamics on the island, already severely damaged by decades of sand mining,” he says.

“Changes in water chemistry and habitat quality in the lagoon have disrupted ecosystems, threatening both the natural beauty of our island and the livelihoods of its inhabitants.”

Mussington is among Barbudans who allege that the Antigua and Barbudan government saw Hurricane Irma as such an opportunity to acquire prime land for developers, and that connecting water and electricity were deliberately delayed to keep Barbudans from returning.

It is “disaster capitalism”, says Mussington. “The prime minister, saying 95% was destroyed and uninhabitable, also estimating $250m to $300m was needed in aid before any assessment was made by the UN, that was not an arbitrary figure, one of the large developments, Paradise Found, required initial investments to that value.

“Until now, one of the main things we kept trying to get from the government was an independently audited account of all goods, services, materials, finances that were sent in name of Hurricane Irma relief. We have never received such an account,” he says.

“The Indian government gave a grant of $1m. It was to go to refurbish the hospital. The government made the decision at the height of the disaster before anything was done, that they were going to use some of the money to repair the post office. So we got a post office repaired before the health facility was.”

Mussington says Barbudans’ land rights have been contested for decades. “It started escalating in 1976 with the Local Government Act. The Antiguan administration began to realise the potential of Barbuda. It was around that time that the sand mining enterprise started, and they began to see the wealth that can be extracted and the speculation with (land) leases then started,” he says.

The Barbuda Land Act of 2007, enacted by Baldwin Spencer’s United Progressive party (UPP) government, was seen as historic legislation to protect people’s rights and communal land ownership.

Barbudans were determined their island would not become like Antigua, where hotels and celebrity mansions are strung across its reputed 365 beaches.

However, enshrining rights in written law left those rights vulnerable to amendments. In 2016, the Browne government, apparently hellbent on large-scale tourism development, dissolved the Barbuda Land Act.

Trevor Walker, a Barbudan MP, told the Antigua Observer that changing the Land Act had been “an unforgiveable sin”.

In its place emerged a law that allowed privatisation without consent of the Barbudan Community Council, fuelling mistrust between the central government in Antigua and Barbudans, who were then permitted to apply for the title to the land they were already occupying.

Barbuda’s national parks manager, Kelly Burton, says: “The Local Government Act is entrenched in the constitution, and that was where the Land Act was formed from. That [Local Government Act] was not repealed because they cannot change the constitution without a two-thirds majority.

“So, instead they went right ahead and repealed the Land Act, and they did what they wanted to do, selling off land in Barbuda.

“Normally, you wouldn’t get land unless you purchase an existing lease. You first have to go to the Barbuda Council, which is the authority, with a letter of intent. A town hall meeting follows, where a majority vote is needed to move forward. The plan then goes to parliament. If they agree, it goes for cabinet approval, and then signed by the British governor general, that’s the process. A lot of these leases that they (developers) receive do not go through that process.”

In 2017, say islanders, Hurricane Irma provided the opportunity to remove the 1,700 “deracinated imbeciles” as Gaston Browne has called Barbudans, who have consistently called for any tourism projects to be low-impact and sustainable.

Jackie Frank, a former chair of the Barbuda Council, whose father was an MP on the committee that devised the original Land Act, believes the prime minister has a different view [of tourism].

“He [Browne] said: ‘Barbuda will be for billionaires, to join that club you need a private jet’. This leaves little room for Barbudans,” she says. “Barbuda is a neglected place. If we accept what’s being done, we don’t just lose the land, we could be removed as a people,” she says.

Browne has said Barbudans will be empowered by owning title deeds to land – land that they already owned in principle.

Mussington disagrees: “He made the statement that any aid received was not for fixing homes but to fix public buildings, so take that title deed and go to the bank and borrow money to fix your house.”

Pointing to a derelict building, he adds: “It has been going on for six years and that is the police headquarters, the seat of law and order on the island, a public building, and that remains just how the hurricane left it. So what was the priority?”

Gulliver Johnson, a local activist, says: “I don’t mind being a servant or cleaner if I have a share in the land, but don’t come here, take my land and then offer me a job to clean your hotel. It is soon going to become apartheid here, where we need a pass to go where the foreigners occupy.”

Many beaches, including Princess Diana Beach, are restricted due to developments. “This is the growing situation on the island, as access to more beaches continues to be restricted with heavy patrolling by security guards and constant monitoring by security cameras to ward off any trespassing Barbudan citizens,” says Johnson.

Alliances between developers and the Antiguan government are a key bone of contention for Barbudans, who claim there is cronyism in the relationships with foreign celebrity investors who are given honorary titles.

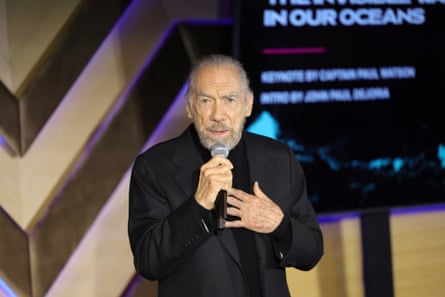

US billionaire John Paul DeJoria – the founder of Paul Mitchell hair products and Patrón tequila – has been appointed ambassador-at-large for Antigua. His Peace, Love and Happiness (PLH) vehicle is developing the large Barbuda Ocean Club with partners JB Turbidy, whose FireSky Ventures is part of the Christophe Harbour luxury resort on St Kitts, and Steve Adelson, whose Discovery Land Company helped develop the similar Baker’s Bay resort in the Bahamas.

This project was first positioned as a relief effort for the island’s recovery. The Barbuda Ocean Club encompasses two ecologically critical areas, Palmetto Point and Coco Point. Palmetto Point will boast 400 luxury villas to be sold for up to $10m; an 18-hole golf course; a beach club; a farm and family park and a social club. About 600 acres (240 hectares)have been delineated. Coco Point is partly operational and fishers have complained their access to the sea has been blocked as a result.

Robert De Niro, co-owner of developers Paradise Found, which occupies the site of disused hotel the K-Club, was named special economic envoy for Antigua by Browne in 2015. This development was briefly stalled by a court challenge to the constitutional legitimacy of the “Paradise Found (Act) 2015”, legislation that overturned previous requirements for developers to consult local people. Trevor Walker and Mackenzie Frank of the Barbuda Council lost the challenge when the privy council ruled they could not demonstrate a documentary interest in the communal property.

The $14m airstrip that is subject to November’s privy council hearing is being built by the Discovery Land Company. The airport is an integral part of all the projects as it will take private jets and potentially charter flights. All developers contribute, with any excess being met by the government.

The challenge to the airstrip is backed by British NGO the Global Legal Action Network (Glan), which has supported islanders’ legal fights since 2019 says the founding director, Gearóid Ó Cuinn.

“The misleading narratives, the forced transfer of native Barbudans, and layers upon layers of questionable conduct, dealings, leases, legislation and political pressures, all raise questions about the integrity and legitimacy of some of these dealings,” says Ó Cuinn. “In the weeks after the hurricane, there was a perfect alignment of private interest and the actions of the government, all for private gain at the expense of those who actually live on the island.”

Conflicts of interest “are not uncommon in these islands”, says Johnson, noting the appointment in 2018 of Browne’s wife Maria Bird-Browne as a minister of housing, works, land and urban renewal. The Development Control Authority (DCA) falls under her authority, making it easy to override any objections from the Department of the Environment.

A major concern for activists has been the lack of due process, from proposals and approvals to construction of several of the multimillion-dollar developments without the consent of the Barbuda Council. Surveys have shown that most Barbudans do not oppose modernisation but are against large-scale unsustainable development that overpowers their own land use and destroys the island’s unique ecosystems.

In December 2020, Glan submitted a complaint about the destruction of wetlands to the Ramsar Secretariat and asked for an independent advisory mission to Barbuda. In 2021, the NGO alerted the UN special rapporteur about the human rights impacts of the developments. Glan has also supported 22 islanders who faced trespass charges after a protest against the Palmetto Point development. The charges were dropped in September 2022.

The Antigua and Barbudan government has threatened protesters with arrest.

“I also want to make it abundantly clear that those who may intend to become economic terrorists in this country, to block investment and retard the progress of the people of this country to keep our people unemployed. They would have to face the full extent of the law for any infractions whatsoever,” Browne hassaid.

As Barbudans wait for yet another court ruling on their rights, the years of fighting have divided people of the 161 sq km (62 sq mile) island. Trucks and heavy machinery have left unpaved roads pockmarked with craters and the layers of dust coating homes in Codrington village are a constant reminder to islanders of the battle they refuse to accept as lost.