The scourge of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) is global. While their consumption is particularly high in the west, forming more than half the average diet in the UK and the US, for example, UPFs are replacing fresh food in diets on every continent.

This month, the world’s largest review on the health threats of UPFs was published in the Lancet. It warned that such foods are exposing millions of people to long-term harm, and called for urgent action. Earlier this year Unicef revealed that more children around the world were obese than underweight for the first time, as junk food overwhelms diets, with the steepest rises in low- and middle-income countries.

Carlos Monteiro, professor of public health nutrition at the University of São Paulo, and one of the Lancet series’ authors, says that profit-driven corporations, not individual choices, are driving the change in habits.

For parents, it can feel like the entire food system is working against them. “Sometimes it feels like we have zero control over what we are putting on to our kid’s plate,” says one mother from India. We spoke to her and four other parents from around the world on the growing challenges and frustrations of providing a healthy diet in the age of UPFs.

Nepal: ‘She craves cookies, chocolate and juice’

Raising a child in Nepal today often feels like trying to swim against the current, especially when it comes to food. I cook at home as much as I can, but the moment my daughter steps outside, she is surrounded by brightly packaged snacks and sugary drinks. She constantly craves cookies, chocolates and packaged fruit juices – products aggressively advertised to children. A single pizza commercial on TV is enough for her to ask, “Can we have pizza today?”

Even the school environment reinforces unhealthy habits. Her canteen serves sweetened fruit juice every Tuesday, which she eagerly awaits. She receives a six-piece biscuit pack from a friend on the school bus and chocolates on birthdays, and faces a chip shop right outside her school gate.

Some days it feels like the entire food environment is working against parents who are simply trying to raise healthy children.

As someone working in the Nepal Non-Communicable Disease Alliance and leading a project called Promoting Healthy Foods in Schools to Reduce NCD Risk Factors, I understand this issue deeply. Yet even with my expertise, keeping my eight-year-old daughter healthy is incredibly difficult.

These repeated exposures at school, in transit and online make it nearly impossible for parents to limit ultra-processed foods. It is not just about children’s choices; it is about a food system that normalises and promotes unhealthy eating.

And the data reflects exactly what families like mine are experiencing. The Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022 found that 69% of children between six and 23 months ate unhealthy foods, and 43% were already drinking sweetened beverages.

These numbers echo what I see every day. A study conducted in the Lalitpur district, where I live, reported that 18.6% of schoolchildren were overweight and 7.1% were obese, figures closely associated with the rise in junk food consumption and increasingly inactive lifestyles. Another study showed that many Nepali children eat sweet snacks or processed savoury foods almost daily, and this regular consumption is tied to high levels of tooth decay.

Nepal urgently needs stronger policies, healthier school environments and stricter marketing regulations. Until then, families will continue fighting a daily battle against junk food – one biscuit packet at a time.

Manita Pyakurel

St Vincent and the Grenadines: ‘Greasy, salty, sugary fast food is the preference’

My situation is a bit unique as I was forced to relocate from an island in our archipelago that was devastated by Hurricane Beryl last year. But it is also part of the stark reality that is facing parents in a region that is feeling the very worst effects of climate change.

Even before Beryl, as a food nutrition and health teacher, I was deeply concerned about the increasing proliferation of fast food restaurants in St Vincent and the Grenadines. Today, even smaller village shops are complicit in the transformation of a country once defined by a diet of healthy locally grown fruits and vegetables, to one where greasy, salty, sugary fast food, packed with artificial ingredients, is the preference.

But the situation definitely worsens if a hurricane or volcanic eruption wipes out most of your vegetation. Fresh, healthy food becomes scarce and very expensive, so it is really difficult to get your kids to eat right.

Despite having a steady job I wince at food prices now and have often resorted to choosing between items such as peas and beans and meat and eggs when feeding my four children. Serving fewer meals or smaller servings have also become part of the post-Beryl coping strategies.

Also it is quite convenient when you are juggling a demanding job with parenting, and rushing around in the morning, to just give the children $2 or $3 to buy snacks at school. Unfortunately, most school tuck shops only offer ultra-processed snacks and sugary sodas. The result of these challenges, I fear, is an increase in the already epidemic rates of lifestyle diseases such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension.

Arlene Williams-Jack, as told to Natricia Duncan

Uganda: ‘It’s in every mall and every market’

The KFC sign looms large at the entrance of Akamwesi, a mall in Mpererwe neighbourhood in Kampala, daring you to pass by without stopping at the drive-through.

Many of the children and parents visiting the mall have never gone beyond the borders of Uganda. They certainly don’t know about the Great Depression that inspired Colonel Sanders to start one of the first American international food chains. All they know is that the three letters KFC represent all things sophisticated.

after newsletter promotion

In every mall and every market, there is fast food for every pocket. As one of the more expensive options, KFC is considered a treat. It is the place Kampala’s families go to celebrate birthdays and baptisms. It is the children’s reward when they get a good school report. In fact, they are hoping their parents take them for Christmas at KFC.

“Mom, do you know that some people pack KFC for school lunch,” my 14-year-old daughter, who attends a school between Mpererwe and the more upscale neighbourhood of Acacia, tells me. She says that on the days they do not pack KFC, they pack food from Café Javas, an east African fast-food chain selling everything from fried breakfasts to burgers.

It is Friday evening, and I am only half-listening as I struggle to do the weekend shopping at Acacia mall while steering her and her brother away from the restaurants suggesting that life would be so much easier if we bought chips and chicken and ate in front of a Netflix movie.

When we get home, I find my husband has already slaughtered one of the free range chickens in our back yard. I hope the aroma of chicken slow boiled for hours and served with fresh vegetables from the market will triumph over the allure of fast food.

Patience Akumu

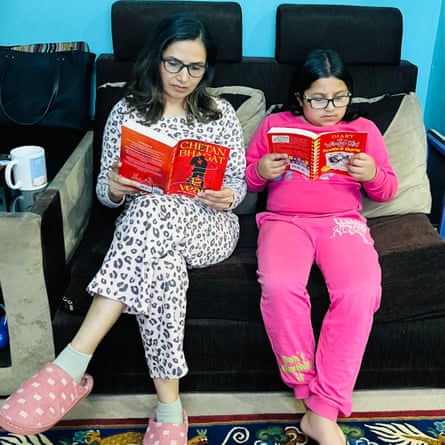

India: ‘It can feel like we have zero control’

When I was growing up, we literally ate everything. There was not much awareness about what was healthy and what was unhealthy. Today, what children can and can’t eat it is a constant conversation – in school, at home, in the news.

My daughter loves ice-cream and chocolates. Her grandparents are very indulgent, and I often have to put my foot down. I try to rationalise the amount she eats, but it is difficult. What I hate most are lollipops. They are sticky, messy and she keeps them in her mouth for hours. Sometimes I give in because it is tiring to constantly be on top of this. As working professionals, it is not always possible to do everything from scratch, such as paneer (homemade cottage cheese). However, a recent scandal surrounding synthetic paneer had me concerned for days, as we source store-bought paneer on a regular basis.

It also does not help that when we go shopping all the treats and chocolates are right at the checkout. My daughter often accompanies me to the store and asks me to buy chocolates or some other packaged snack. Even things like peanut chikki (like a brittle) that I grew up eating are highly processed today. If I say no, she sulks a little, saying I always say no.

The rule in our home is no refined sugar, no fizzy drinks. That means no biscuits, which are basically made of maida (refined flour) and palm oil. My doctor tells me it sticks to children’s teeth and gives them cavities. But when someone else offers them, she goes nuts.

I try to read the ingredients on the packaging, and anything that lists more than 10, I don’t buy.

Sometimes it feels like we have zero control over what we are putting on to our kid’s plate and that sense of helplessness is very frustrating.

Moreover, there are very few options available for wholesome snacks in the Indian market and they are very pricey. So, economically speaking, it is also a constant challenge to ensure my child is eating healthy and balanced meals all the time.

Amoolya Rajappa, as told to Anuradha Nagaraj

Kenya: ‘One bite and he was hooked’

My son says it all started when he saw his friends eating things he knew he wasn’t allowed to. One bite and he was hooked. He was probably nine. The Indonesian noodles were one of the tastiest things he had ever eaten, he told me. Having heard and read what these foods were doing to the health of young people around the world, I was not happy.

But that initial taste piqued his curiosity and he started trying to introduce instant noodles to the weekly shop – by stealth. Our nearby mall was the crime scene. During one visit, he snuck a pack of beef-flavoured noodles from either Singapore or South Korea, burying it under other items. I was too distracted to notice.

He repeated the move during another shopping trip. This time I was keen enough to notice not one, but three packets of UPFs in the trolley. He had to return them to the shelves, much to the consternation of other shoppers queueing at the checkout.

But just removing such items from the shopping basket is not enough. What do you replace them with? So many exotic treats that appeal to children carry health risks. I sat in a recent media briefing where an eye doctor said that many young people presenting with eyesight issues are being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. “They come for an eye checkup but unknown to their parents, diabetes is the root cause of the eyesight issues,” she said. “Junk food is at the centre of the declining health among young people in Kenya.”

While local markets abound with healthy foods such as tubers and traditional vegetables, it has been a constant battle getting my son, now 14, to eat them.

Happily, he is slowly adjusting to healthy eating habits. “It comes with age,” he joked recently. “Junk food is really appealing but it doesn’t help much. You could eat all you want but after about an hour you’ll have to eat ugali [stiff dough made of maize flour] and sukuma wiki [a dish made using greens] – to fill you up.”

Peter Muiruri